2025 Startup Market Lessons: Compliance, Funding & Profit

By Filing Buddy . 20 Jan 26

The Tale of Two Bells

The sound that defined the Indian startup ecosystem in 2025 was not the clinking of champagne glasses in a Bangalore pub, nor was it the confident hum of a PowerPoint projector in a Sequoia boardroom. It was the sound of a bell ringing at the Bombay Stock Exchange (BSE), echoing against the deafening silence of shuttered offices in Gurugram and Mumbai.

In August 2025, the listing ceremony of a prominent electric vehicle manufacturer promised to be the coronation of India’s manufacturing ambition. The air was thick with the scent of marigolds and the palpable electricity of retail investor hope. Yet, barely months later, that same stock ticker would flash red, bleeding value day after day, a digital testament to broken promises and service failures. Contrast this with the quiet, almost funereal dismantling of the Good Glamm Group once a $1.2 billion unicorn darling where lenders, not founders, called the shots, auctioning off brands like furniture in a fire sale.

These two scenes, the volatile public market debut and the private market implosion bookend a year that history will record as The Great Recalibration. If 2021 was a year of intoxicating excess and 2023 a year of freezing winter, 2025 was the year the Indian startup ecosystem finally sobered up. It was a year where the "growth at all costs" mantra didn't just fail; it was actively punished. The ecosystem didn't die; it grew up. It traded the adolescence of valuation-chasing for the adulthood of tax-paying, profit-generating, and regulatory compliance.

Nut Graph: The Year of Consequence

The data from 2025 paints a picture of a market in transition, not retreat. While total funding stabilized between $11 billion and $13 billion a fraction of the $42 billion peak of 2021 the composition of that capital shifted dramatically. The ecosystem witnessed a paradox: funding volumes dipped, yet the market saw a record 18 IPOs, unlocking over INR 41,000 Crore in liquidity.

This divergence signals a fundamental maturation. The market has bifurcated into the "haves" companies with sustainable unit economics and governance standards rewarded by public markets and the "have-nots" venture-fueled giants that collapsed under the weight of their own unsustainable ambitions. As we analyze the debris and the monuments of 2025, three distinct lessons emerge that will define the next decade of Indian entrepreneurship:

- The Public Market Verdict: The "Private Premium" is dead. Public markets are ruthless auditors that punish lack of governance and profitability (e.g., Ola Electric) while rewarding execution and manufacturing competence (e.g., Ather Energy).

- The Sovereignty of Domicile: The era of "global" Indian startups domiciled in Delaware or Singapore has ended. The "Reverse Flip" wave proves that long-term value creation in India requires being an Indian company, even if it costs hundreds of millions in taxes.

- The Pivot to Substance: The low-hanging fruit of the consumer internet is gone. The next trillion dollars of value will come from deep science and "hard tech" space, defense, and high-IP innovation rather than another 10-minute delivery app.

We will dissect the failures of Dunzo and Good Glamm, the triumphs of Zomato and Ather, and the quiet revolution in India’s space sector to understand where the ecosystem goes from here.

Lesson 1: The Public Market Verdict Profitability or Perish

The Death of the Private Premium

For the better part of a decade, the "Private Premium" was an accepted reality of the startup world. A company could command a higher valuation in the private markets based on GMV (Gross Merchandise Value) multiples and future growth narratives than it ever could in the public markets, which typically trade on PE (Price-to-Earnings) or EBITDA multiples. 2025 was the year this premium inverted.

The Indian public markets, buoyed by domestic liquidity from mutual funds and retail investors, began to offer "scarcity premiums" to high-quality tech stocks, while simultaneously de-rating companies that failed to deliver on their promises. The listing of 18 new-age tech companies provided a large enough sample size to draw definitive conclusions: the Indian investor is sophisticated, impatient, and unforgiving.

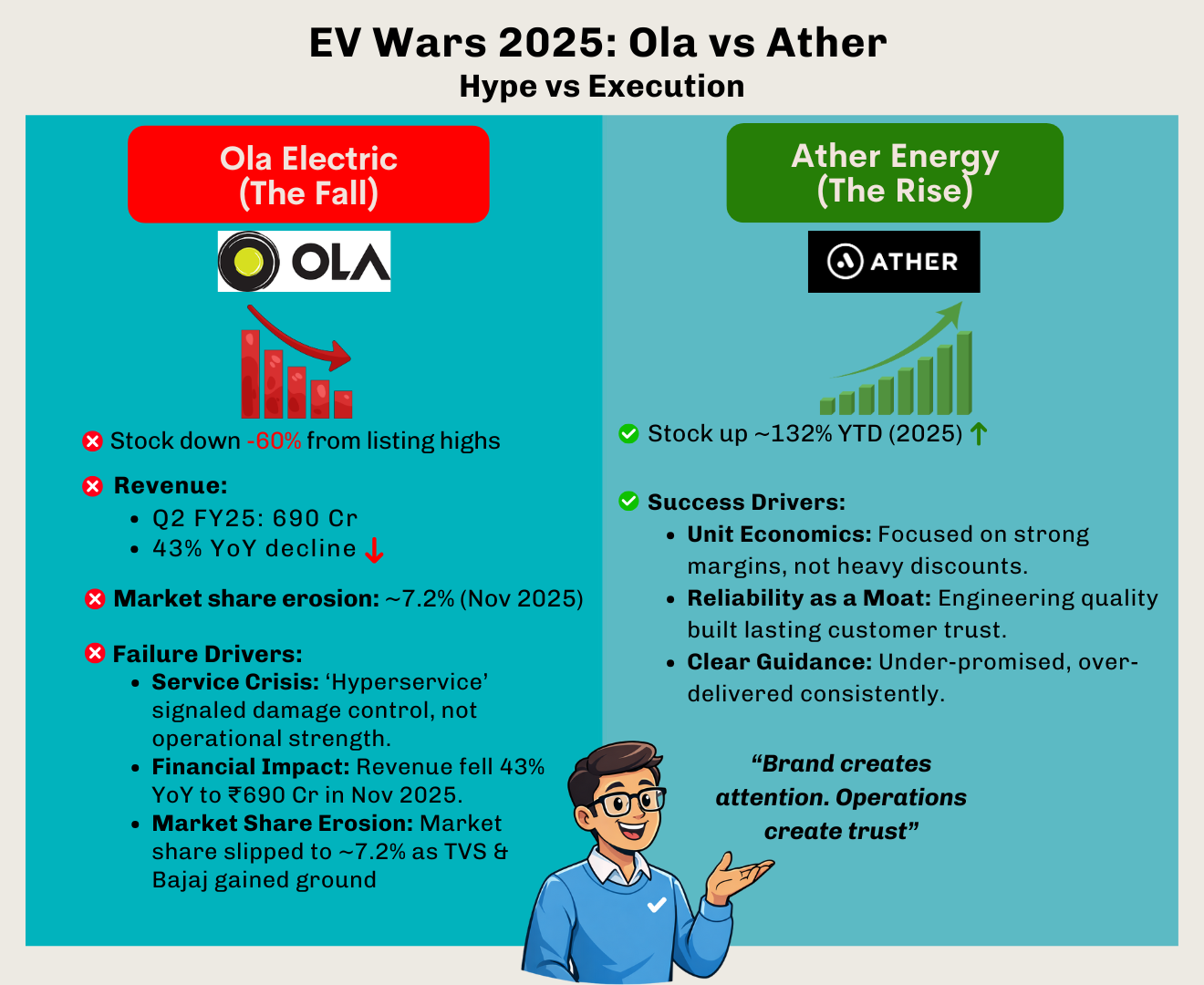

Case Study: The EV Divergence (Ola Electric vs. Ather Energy)

The most instructive contrast of 2025 played out in the electric vehicle sector. Both Ola Electric and Ather Energy are pioneers, yet their fortunes on the stock market diverged violently, offering a masterclass in what the market now values.

The Unraveling of Ola Electric

Ola Electric entered 2025 as the undisputed market leader in volume, banking on a narrative of vertical integration and aggressive scale. It was listed in August 2024 with a valuation that was priced in perfection. By late 2025, the stock had crashed approximately 60% from its listing highs.

The Mechanism of Failure:

The collapse was not triggered by a lack of demand for EVs, but by a failure of manufacturing competence and service infrastructure. As Ola pumped thousands of scooters into the market, its service network cracked. Social media platforms were inundated with customer complaints regarding software glitches, battery issues, and, most critically, the unavailability of spare parts.

The Service Crisis: In a desperate bid to stem the reputational bleeding, Ola launched "Hyperservice," a program deploying 250 rapid-response teams. While intended to demonstrate responsiveness, the market interpreted it as an admission of deep structural failure. A manufacturing company should not need "rapid response teams" to fix its core product; the product should work.

Financial Impact: The service woes hit the top line. In Q2 FY25, Ola's revenue plummeted 43% year-over-year to INR 690 crore, down from INR 1,214 crore in the previous year.

Market Share Erosion: Legacy players like TVS and Bajaj, who had been criticized for moving too slowly, vindicated their strategy. They ate into Ola’s market share, which slipped to single digits (~7.2%) in November 2025.

The Market's Verdict: You cannot "software update" your way out of hardware problems. The public market penalized Ola for treating a manufacturing business like a software business.

The Vindication of Ather Energy

In sharp contrast, Ather Energy, often criticized for its slower rollout and higher price points, became the darling of the street. The stock gained approximately 132% year-to-date in 2025.

The Mechanism of Success:

Unit Economics: Ather focused on reducing losses per unit and maintaining gross margins. They refused to engage in the deep discounting that characterized the early EV wars.

Reliability as a Moat: Ather’s reputation for engineering quality meant it faced none of the service headwinds that plagued Ola. As the early adopters of EVs moved to the mass market, "reliability" replaced "novelty" as the primary purchase driver.

Clear Guidance: Ather’s management consistently under-promised and over-delivered on production targets, building credibility with institutional investors who crave predictability over hyperbole.

Insight: In 2025, the market decided that "Growth" is a commodity, but "Governance and Quality" are assets. The premium shifted to the latter.

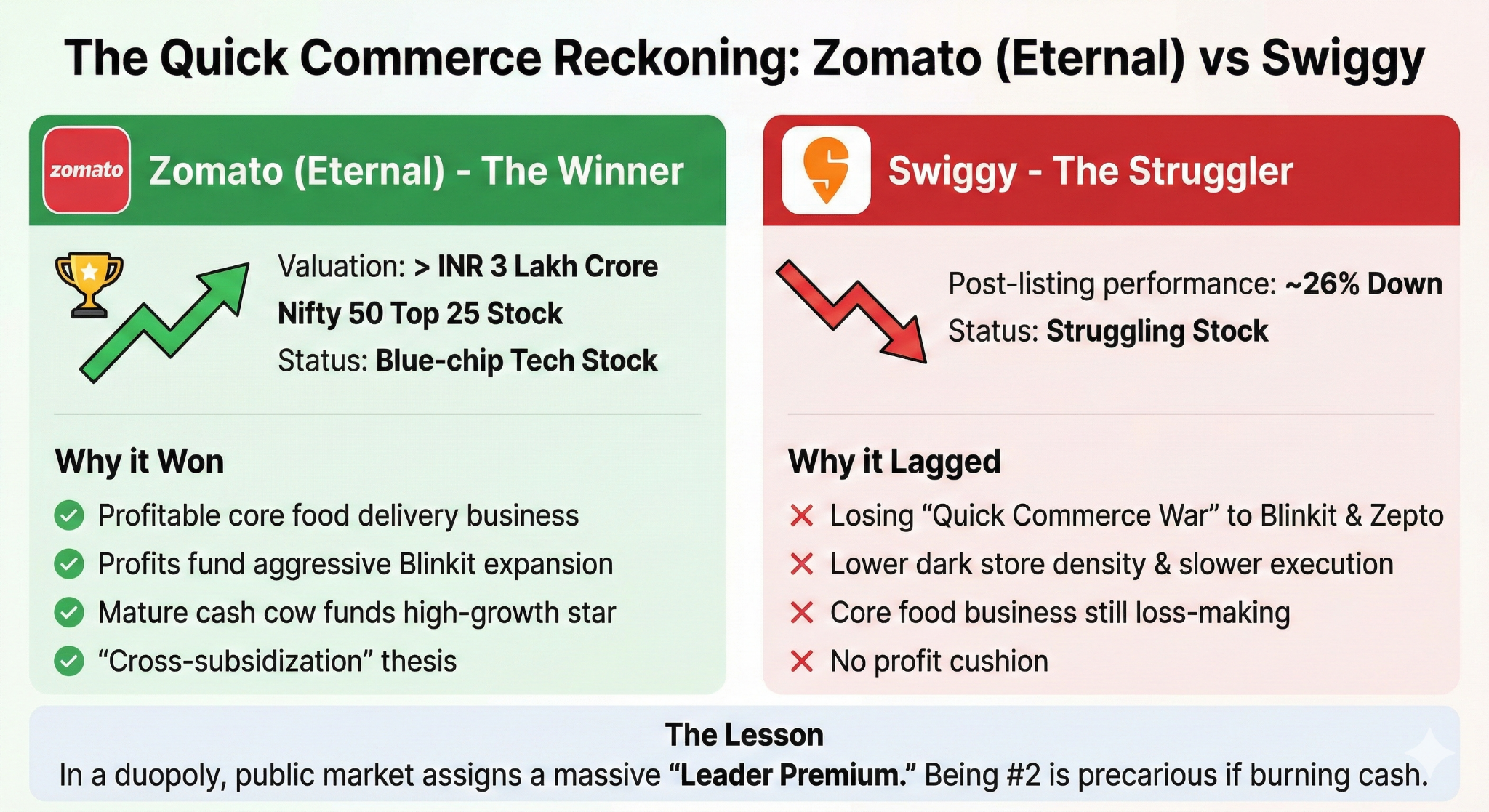

The Quick Commerce Reckoning: Swiggy vs. Zomato (Eternal)

The food delivery and quick commerce duopoly also faced the public market test, revealing a preference for market leadership and profitability.

Zomato (Eternal): The company, having rebranded to "Eternal" to reflect its multi-business structure, solidified its position as a blue-chip tech stock. With a valuation surpassing INR 3 Lakh Crore, it entered the top 25 stocks of the Nifty 50.

Why it Won: Zomato achieved profitability in its core food delivery business, which effectively subsidized the aggressive expansion of Blinkit, its quick commerce arm. Investors bought into the "cross-subsidization" thesis that the mature cash cow (food) could fund the high-growth star (quick commerce).

Swiggy: Listing later in the cycle, Swiggy’s stock struggled, trading down ~26% post-listing.

Why it Lagged: Despite being a pioneer, Swiggy was perceived to be losing the "Quick Commerce War" to Zomato's Blinkit and the unlisted Zepto in terms of dark store density and execution speed. Furthermore, Swiggy’s continued losses in its core food business meant it lacked the "profit cushion" that Zomato offered.

The Lesson: In a duopoly, the public market assigns a massive "Leader Premium." Being #2 is a precarious position if you are burning cash to stay there.

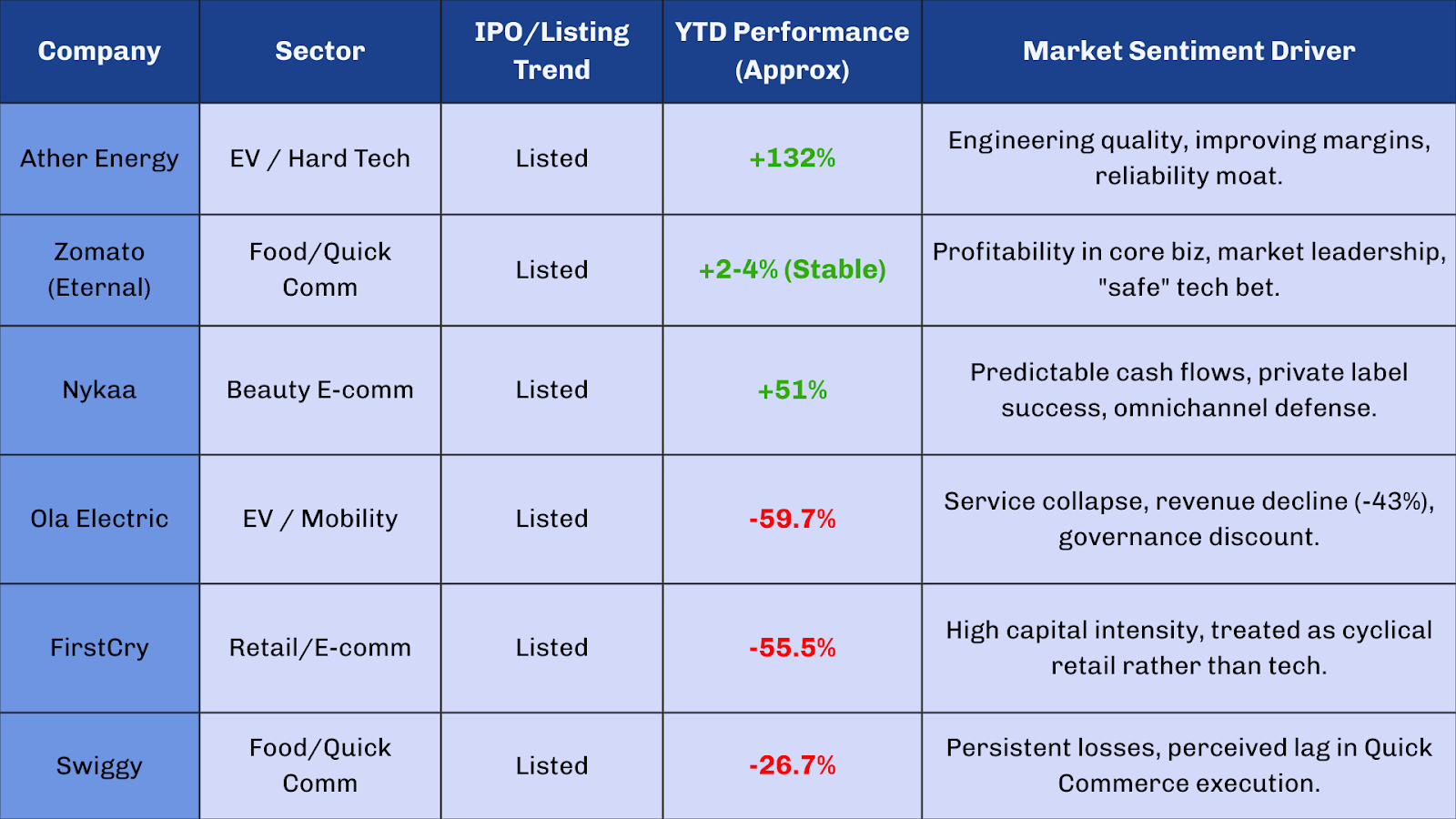

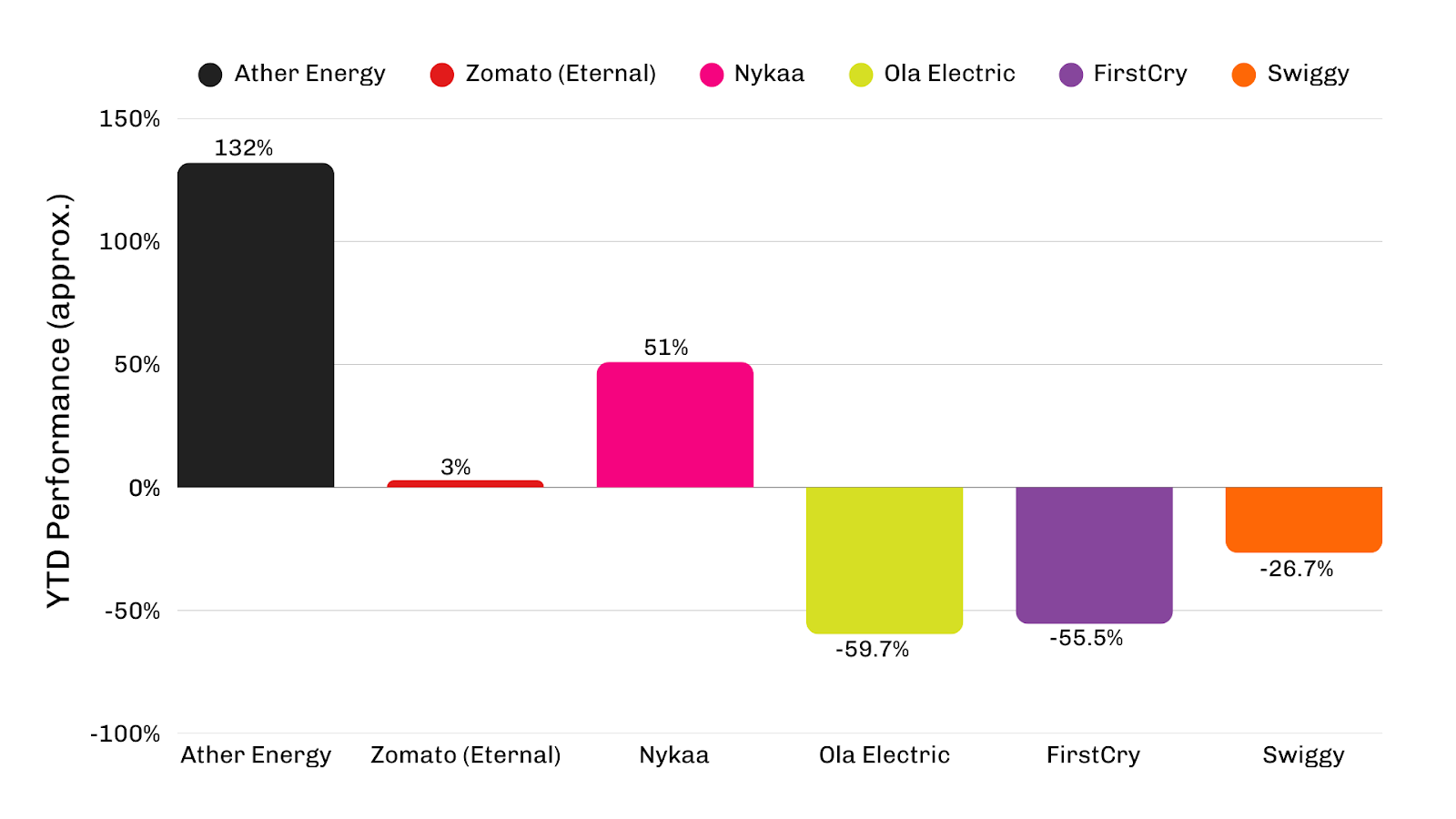

Table 1: The 2025 Public Market Scorecard

Lesson 2: The House of Cards Collapses : The Failure of Financial Engineering

If the public markets provided the discipline of price, the private markets provided the discipline of failure. 2025 saw the dramatic implosion of business models that were built on the shaky foundations of cheap capital and financial engineering rather than fundamental value creation.

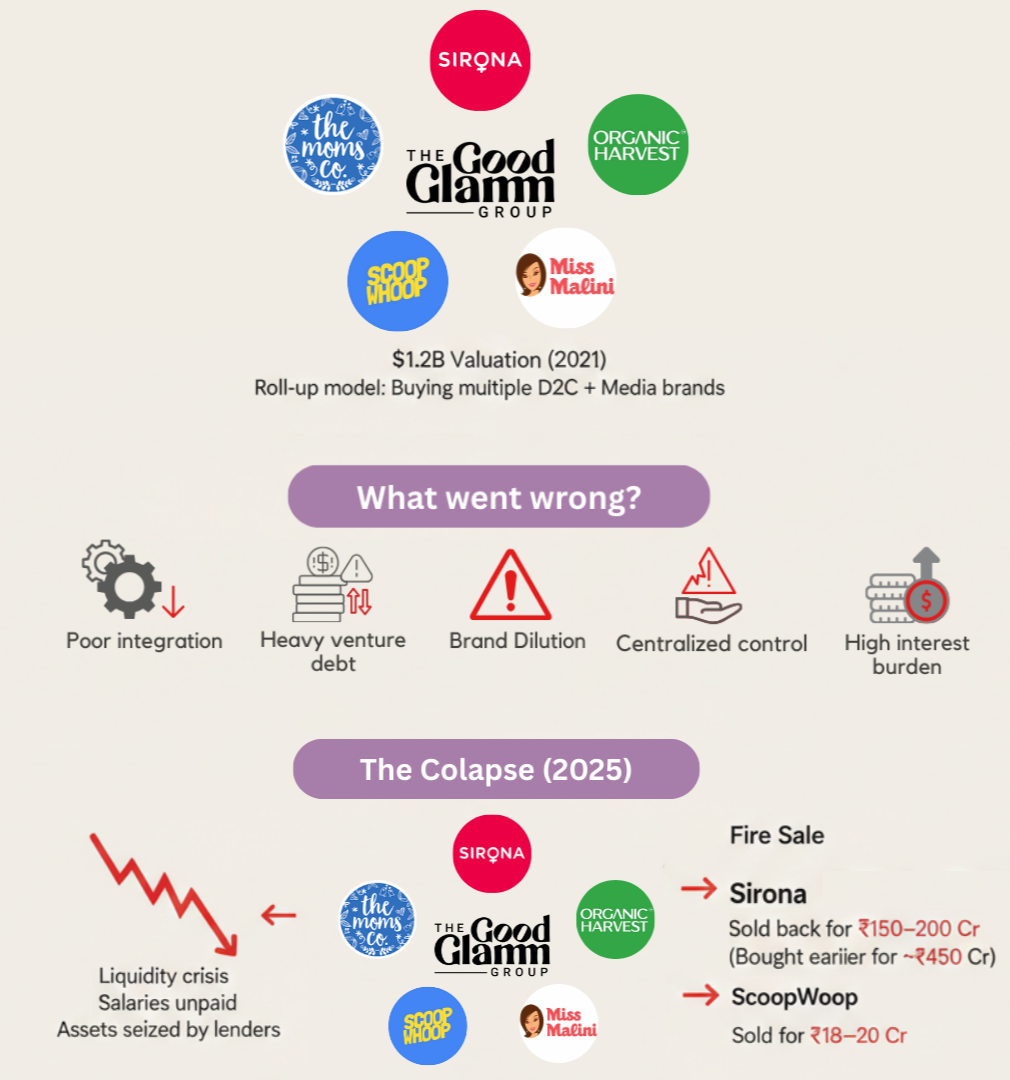

The Good Glamm Group: Anatomy of a Roll-Up Disaster

The most spectacular failure of 2025 was the dismantling of the Good Glamm Group. At its peak in 2021, it was valued at $1.2 billion, the poster child for the "Thrasio-style" roll-up model in India, a strategy of acquiring multiple D2C (Direct-to-Consumer) brands and scaling them through shared marketing and logistics. By 2025, it was a carcass being picked clean by lenders.

The Strategy that Failed:

The group engaged in an aggressive acquisition spree between 2021 and 2023, buying brands like Sirona (feminine hygiene), The Moms Co. (baby care), Organic Harvest, and media assets like ScoopWhoop and Miss Malini. The thesis was that owning the "content" (media) would drive low-cost customer acquisition for the "commerce" (brands).

The Execution Gap:

Integration Nightmare: Instead of synergies, the acquisitions created operational silos. The group centralized functions like marketing and product development, which alienated the founders of the acquired brands. Reports emerged of product formulations being changed to cut costs, destroying the very brand equity they had purchased.

The Debt Trap: Much of this spree was financed through venture debt from lenders like Stride Ventures, Trifecta Capital, and Alteria Capital. When the funding winter hit and equity capital dried up, the interest burden became unsustainable.

The Collapse:

In early 2025, a critical deal to sell one of the brands fell through when the acquirer's CEO stepped down. This triggered a liquidity crisis. Salaries went unpaid for months. Lenders enforced their rights, seizing assets to recover their dues.

The Fire Sale: The group was dismantled piece by piece. Sirona was sold back to its original founders for INR 150-200 crore, a fraction of the ~INR 450 crore Good Glamm had paid for it. ScoopWhoop was offloaded for a paltry INR 18-20 crore.

The Founder's Apology: Founder Darpan Sanghvi issued a public apology, pledging his future earnings to a restitution fund, a rare admission of total defeat in an ecosystem known for spinning failures as "pivots".

The Lesson: You cannot buy a business model. A "House of Brands" requires deep operational expertise to manage diverse categories. Financial engineering (using debt to buy revenue) works in a ZIRP (Zero Interest Rate Policy) world; in a high-interest world, it is a death sentence.

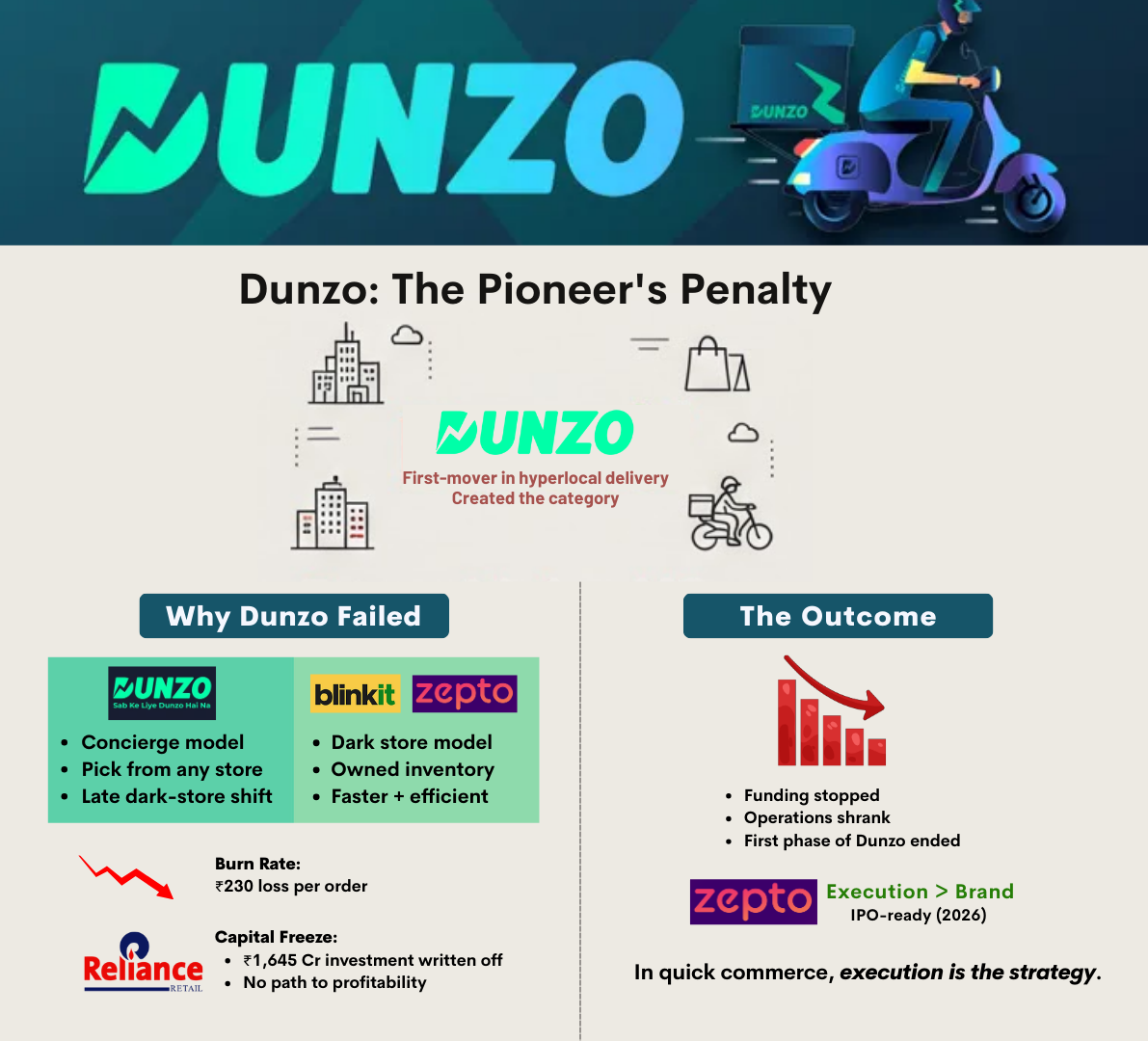

Dunzo: The Pioneer’s Penalty

Reliance Retail's decision to write off its entire INR 1,645 crore ($200 million) investment in Dunzo marked the official end of the first phase of India’s quick commerce evolution.

Why Dunzo Failed:

Dunzo had the first-mover advantage, creating the category of hyperlocal delivery. However, it suffered from a classic "identity crisis."

Concierge vs. Dark Store: While competitors like Zepto and Blinkit went all-in on the "dark store" model (owning the inventory to control speed and margins), Dunzo clung to its "pick up from any store" concierge roots for too long. When it finally pivoted to Dunzo Daily (dark stores), it was too late.

Burn Rate: At its peak, Dunzo was losing INR 230 per order. It lacked the capital efficiency of Zepto or the cross-subsidization power of Zomato/Swiggy.

The Capital Freeze: Reliance, despite owning 26%, refused to fund a bottomless pit without a clear path to profitability. The valuation mismatch between founders and investors prevented external fundraising, leading to a slow, painful asphyxiation.

Comparison with Zepto:

Zepto, conversely, thrived in 2025, completing a reverse flip to India and preparing for a 2026 IPO.Zepto’s success highlighted that in operationally complex businesses like quick commerce, execution is the only strategy. Dunzo had the brand; Zepto had the discipline.

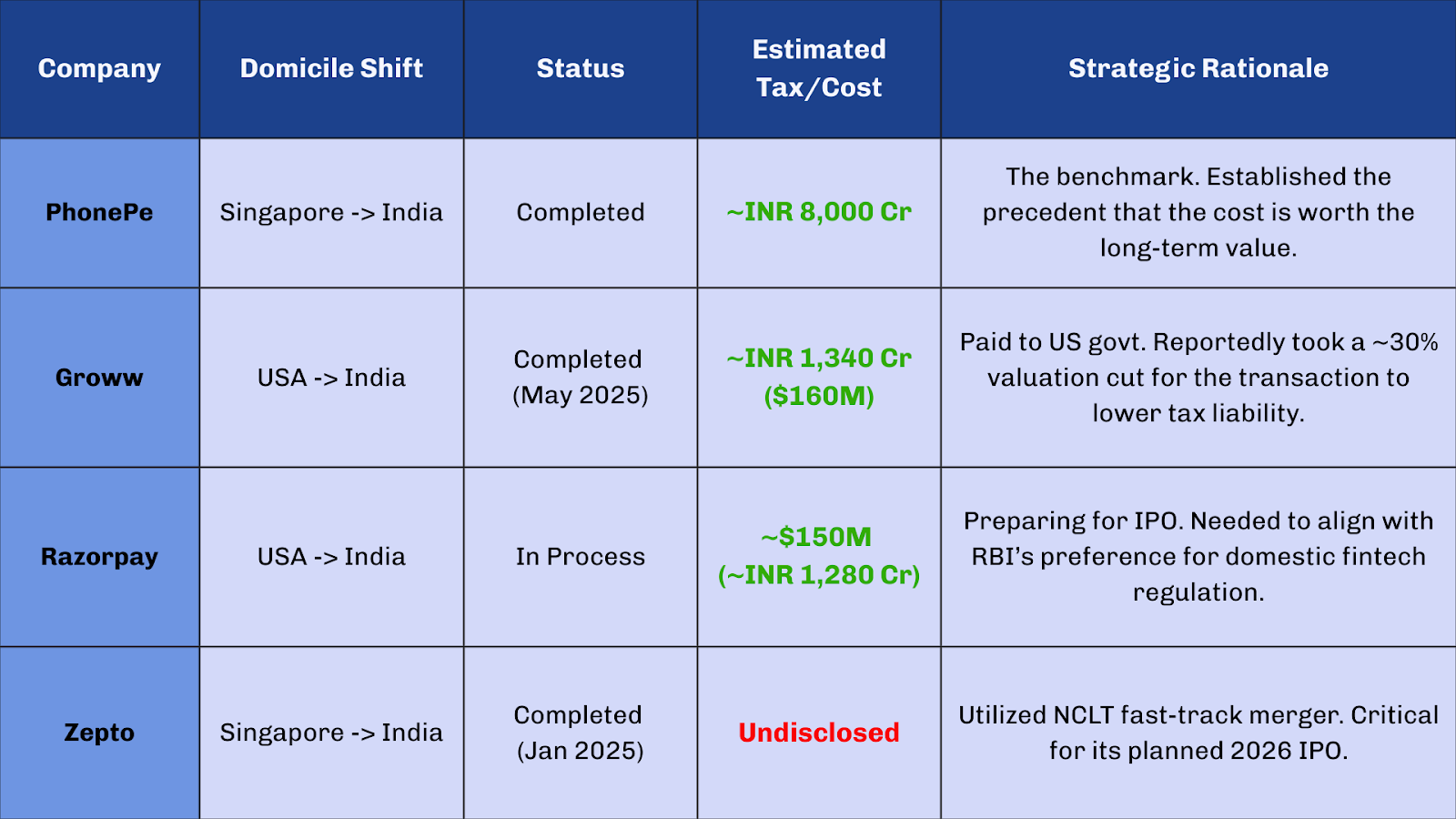

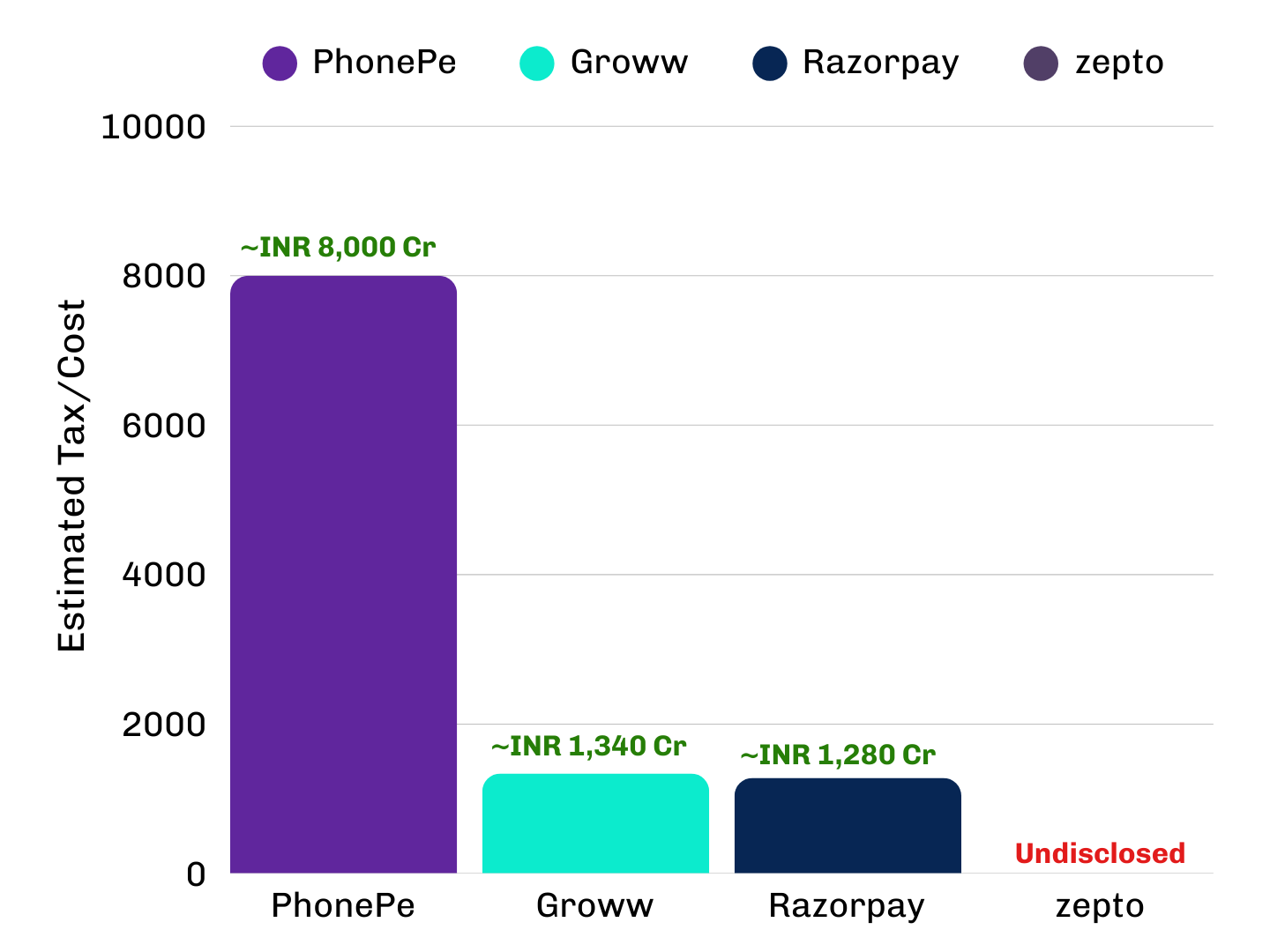

Lesson 3: The Sovereignty of Domicile : The Great Homecoming

For a decade, the standard advice from legal firms and VCs to Indian founders was: "Incorporate in Singapore or Delaware. It’s easier to raise money, easier to do M&A, and the tax laws are predictable."

2025 turned this wisdom on its head. The year was defined by the "Reverse Flip" , the mass migration of India’s most valuable startups back to Indian domicile. This was not a trickle; it was a stampede involving Zepto, Groww, Pine Labs, Razorpay, Flipkart, and Meesho.

The "India Premium" Thesis

Why would rational economic actors voluntarily pay hundreds of millions of dollars in taxes to move into a high-tax jurisdiction? The answer lies in the "India Premium."

Founders and investors realized that the Indian public markets were willing to value their companies at significantly higher multiples than the US markets. In the US, a company like MapmyIndia or a mid-sized fintech might be ignored as a "small-cap" stock. In India, it is treated as a scarcity asset, commanding high P/E multiples driven by the massive inflows from domestic SIPs (Systematic Investment Plans).

Expert Voice: Legal & Tax Consensus

"Reverse flipping is not just a compliance exercise. It is a strategic leap, a statement of belief in India's future. For companies ready to lead in the next phase of India's economic story, coming home is not merely a choice, but a strategic advantage."

The Tax Check: The Cost of Return

The reverse flip triggers a tax event because shares in the foreign holding company are swapped for shares in the Indian entity. The Indian tax authorities view this share swap as a "transfer" of capital assets, liable for capital gains tax.

Table 2: The Cost of the Reverse Flip (2025 Estimates)

Regulatory Context: The RBI’s "Velvet Hammer"

The return to India was also driven by the increasing assertiveness of the Reserve Bank of India (RBI). In 2025, the RBI made it clear that "regulatory arbitrage" operating in India while being governed by foreign boards was no longer acceptable for strategic sectors like payments and lending.

Key Regulatory Moves in 2025:

- Ban on Foreclosure Charges: On July 2, 2025, the RBI issued a directive banning foreclosure (prepayment) charges on floating-rate loans for individuals and MSMEs, effective Jan 1, 2026. This regulation dismantled a lazy profit center for many lenders, forcing them to compete on product value rather than lock-ins.

- SRO Status: The RBI granted Self-Regulatory Organization (SRO) status to the Fintech Association for Consumer Empowerment (FACE), signaling a shift toward formalizing the sector. Startups realized that influencing policy and ensuring compliance was impossible from an office in Delaware

Lesson 4: The Pivot to Substance Deeptech and the "Hard" Problems

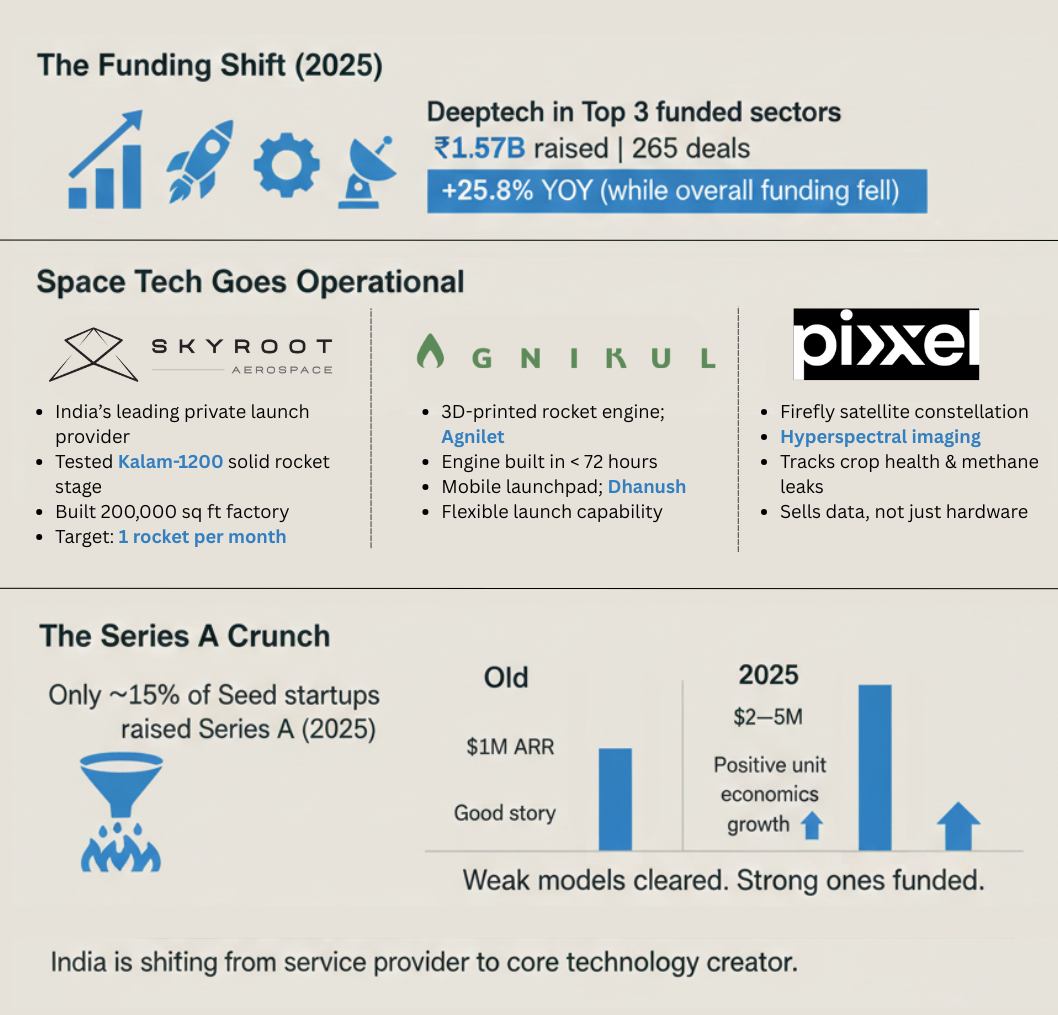

As the door closed on the era of "easy money" for consumer apps, a massive window opened for Deeptech. For the first time, Deeptech entered the top three funded sectors in India, raising $1.57 Billion across 265 deals, a 25.8% increase in a year where overall funding fell.

This shift represents a fundamental change in the risk appetite of Indian VCs. Investors are no longer looking for the next "Uber for X"; they are looking for the "SpaceX of India."

Space Tech: From PowerPoint to Pad

The Indian space sector, liberalized just a few years ago, saw its private players move from "promising startups" to "operational aerospace companies" in 2025.

Skyroot Aerospace:

The Hyderabad-based company solidified its position as India’s leading private launch provider.

The Milestones: While the maiden orbital launch of its flagship Vikram-1 rocket slipped to early 2026, the company achieved critical ground tests. It successfully tested the Kalam-1200, India’s largest private solid propulsion stage, and the carbon-composite payload fairing.

The Strategy: Skyroot is not just building rockets; it is building a "launch cadence." With a new 200,000 sq ft manufacturing facility (Infinity Campus), it aims to produce one rocket per month, targeting the global small-satellite launch market.

Agnikul Cosmos:

Agnikul continued to push the boundaries of manufacturing with its Agnilet engine, the world’s first single-piece 3D-printed semi-cryogenic rocket engine.

The Innovation: 3D printing allows Agnikul to print an engine in less than 72 hours, a process that traditionally takes months. In 2025, they also advanced their "mobile launchpad" concept (Dhanush), which offers strategic flexibility for defense applications, allowing launches from multiple locations rather than a fixed spaceport.

Pixxel:

Moving beyond hardware, Pixxel deployed its Firefly constellation of hyperspectral satellites. The company began commercializing data that can see "invisible" details like crop health and methane leaks marking the transition of the sector from "building infrastructure" to "selling insights".

The "Series A Crunch" and the New Metrics

The pivot to Deeptech coincided with a brutal tightening of the filter for early-stage consumer companies. 2025 was defined by the "Series A Crunch."

The Great Filter: Data shows that only ~15% of startups that raised Seed funding in 2022-2023 managed to raise a Series A round in 2025.

The New Bar: The benchmark for Series A shifted from "promise" to "proof."

Old Standard: $1M ARR (Annual Recurring Revenue) + Good Story.

2025 Standard: $2M-$5M ARR + Positive Unit Economics + 25% MoM growth.

Impact: This crunch acted as a forest fire, clearing out the underbrush of weak business models (the 730 shutdowns) and allowing nutrients (capital) to flow to sturdier trees (Deeptech, B2B SaaS, Manufacturing).

Expert Voice: Prashanth Prakash, Accel

"Advanced manufacturing can give India sovereign leverage by owning intellectual property (IP) and production capability rather than relying on imported technology. This represents a shift from being a service provider to becoming a creator of core technologies."

Reality Check: The 2025 Scorecard

To fully understand the magnitude of the shift, we must look at the aggregated data. The numbers reveal a smaller but far more efficient ecosystem.

Funding & Shutdowns

Total Funding: Estimates range from $11 Billion to $13 Billion. This is an ~8-10% drop from 2024, but a stabilization after the freefall of 2023.

Deal Volume: Remained stable (~936 to 1,250 deals), indicating that while check sizes are smaller, the activity at the Seed stage is vibrant.

Shutdowns: 730 startups shut down in 2025. While a high number, this is an 81% drop from the 3,903 shutdowns in 2024. This suggests that the "Great Cleansing" of the ecosystem is largely complete.

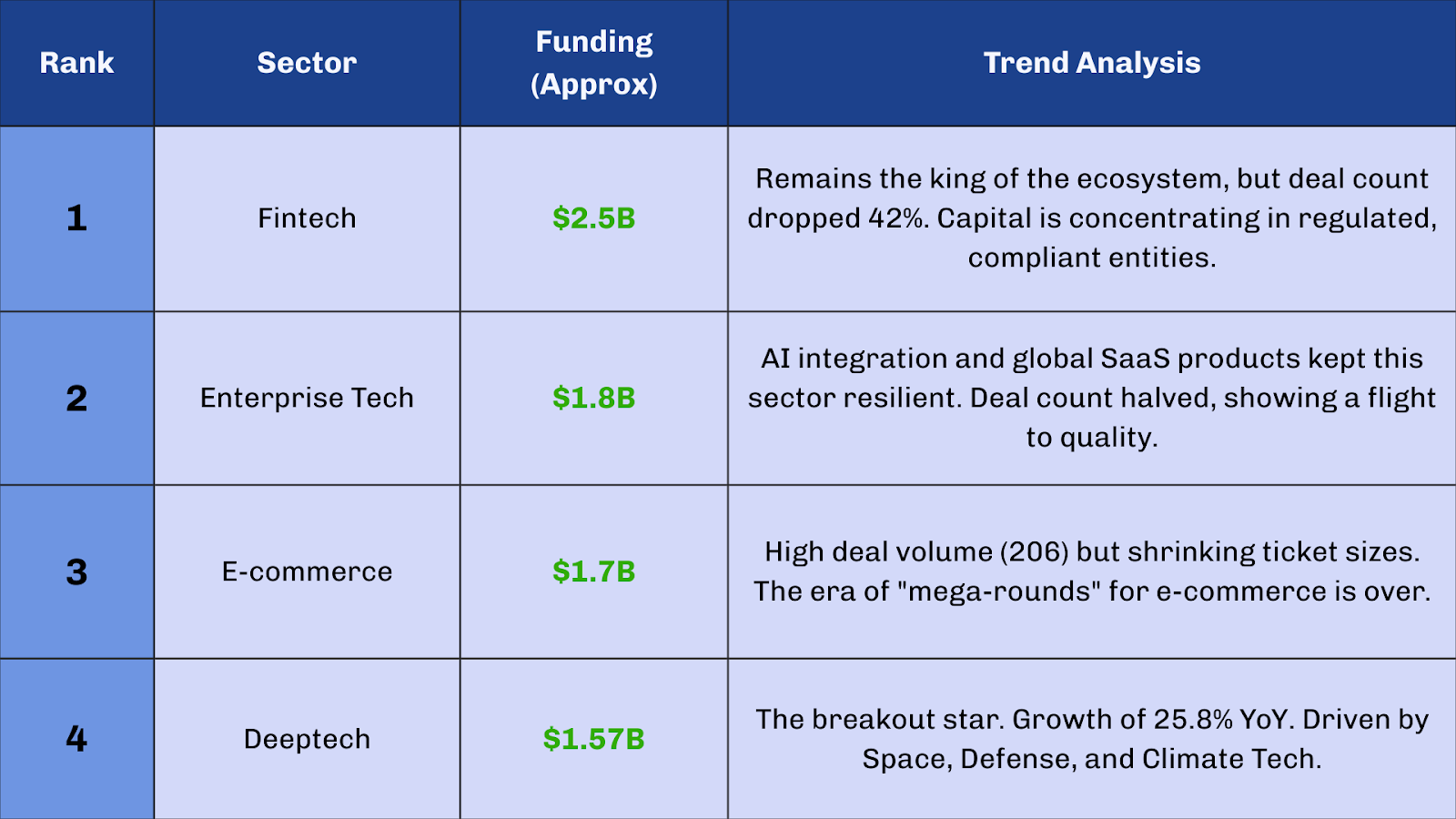

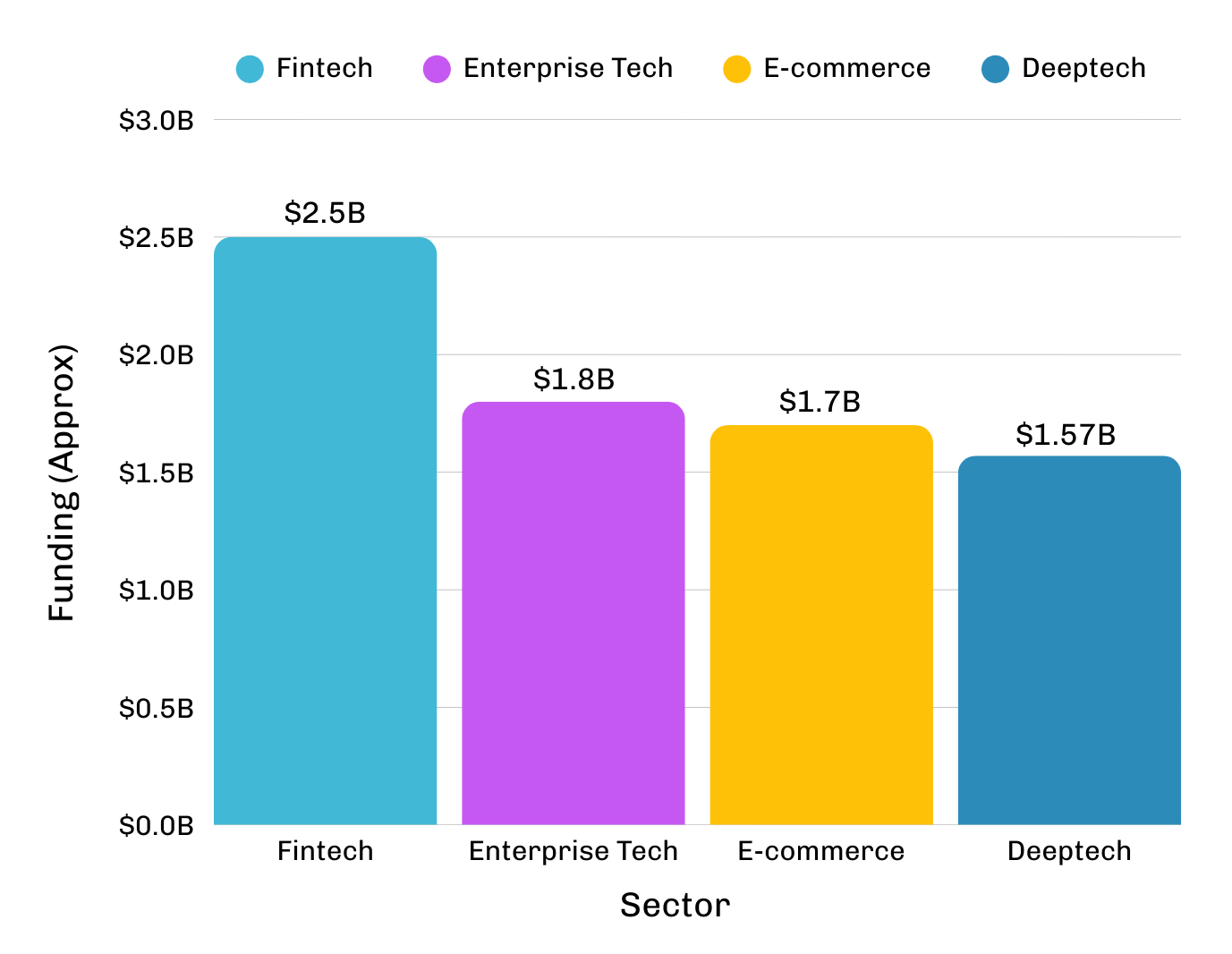

Sectoral Hierarchy (By Investment Volume)

The End of Innocence

As the sun sets on 2025, the Indian startup ecosystem looks fundamentally different from the one that entered the decade. The innocence is gone. The belief that "valuation is value" has been shattered by the collapse of Good Glamm and the slide of Ola Electric. The notion that "global is better" has been replaced by the expensive but necessary patriotism of the Reverse Flip.

But in losing its innocence, the ecosystem has gained something far more valuable: Resilience.

The companies that survived the funding winter of 2023 and the public market scrutiny of 2025 are not fragile flowers; they are cockroaches tough, adaptable, and built to survive nuclear winters. The founders of 2026 are not pitching "Uber for X." They are pitching "Rocket Engines for the World" and "AI for Healthcare."

The "Great Recalibration" was painful. It cost thousands of jobs and billions in written-off wealth. But it cleared the fog. What remains is a leaner, harder, and more serious ecosystem. The party is over, but the real, hard work of nation-building through technology has just begun.

Outlook for 2026:

Watch for the first commercial orbital launches from Indian private players.

Watch for the continued dominance of Zomato as it creates a "super-app" of consumption.

And watch for the "Series A Crunch" to produce a cohort of startups in 2026 that are born profitable, bypassing the burn cycle entirely. The Indian startup story isn't over; it's just moving from the Fiction section to Non-Fiction.

Contact Us

An expert will call you within 24 hours. No payment required to get started.

Related Post

.png)

Why Do 9 In 10 Startups Fail in India?

Learn how from science exhibitions in schools to the hostel rooms of IITs and IIMs, each day a startup is born. Also, explore the reasons for failed startups in India.

. 5 min read.png)

Startup India Fund Scheme- How to Apply, Features, Benefits

Discover this scheme's contribution to the growth of early-stage startups through seed funding, mentoring, networking, and others.

. 3 min read.png)

4 Common Reasons Why Businesses Need to Amend Their Registered Trademark

Learn why businesses often need to make amendments to their registered trademarks. Discover the importance of trademark name search for business identity and the procedure for making changes in India.

. 5 min read